<a id="sokRibbon" href="/contributors/heather-turgeon/"><img alt="sok_ribbon.png" src="http://cdn4.www.babble.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/05/075030a94b25ce80ba184b4b376e5cfa.png" /></a>By now you know the importance of talking to your baby early and often: while she scoops cheerios in her highchair, during a stroll in the park, on the changing table. But that’s only the half of it; it’s equally important to know <em>how</em> to talk to your baby. First of all, the amount of <a href="http://babylab.psych.cornell.edu/wp-content/uploads/2009/04/goldstein-et-al-2003.pdf" target="_blank">language our little ones hear has a big impact on their development</a>. For example, kids growing up in families on welfare hear an average of 600 words an hour, those in working-class families hear 1,250 words an hour, and those in professional families hear roughly 2,100 words an hour. That means every year, a child from a family receiving welfare hears 3.2 million words while the average child in a professional home hears 11 million. This word gap correlates with lingual ability later in life: at age three, kids in professional families have vocabularies of roughly 1,100 words, with children in the lowest economic bracket speaking roughly 500 words. The amount of language directed at kids in the first three years of life is estimated to account for half of the variance in cognitive performance and vocabulary at age 3 and age 9. As a parent, your initial reaction to hearing this is to dial up the talking in your home. And many of us have: I see diligent parents all the time, providing running commentary and narration with their babbling companions in tow. But with a closer look at the research, encouraging parents to talk to their babies turns out to be an oversimplified piece of advice — and one that actually misses many of the critical aspects of vocabulary development for the youngest children. A barrage of words is not the gold standard. In fact, it probably gets in the way of an even more important process for our children’s language learning. <img style="float: right; padding: 10px;" alt="Hearing a whole bunch of words doesn’t do a baby much good, unless the parent is actually helping the baby make sense of them." src="http://cdn4.www.babble.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/06/The-Science-of-Talking-to-Your-Baby.jpg" /> To understand how babies acquire language, psychologists at NYU videotape and analyze parent-baby interactions and track babies’ development over time. They find that a parent’s language does indeed play a big role in shaping how fluent their children become, but <em>parents’ response</em> to baby language is what makes the difference. In one experiment with moms and their 9- or 13 month-olds, researchers showed that a baby’s verbal prowess was related to <a href="http://steinhardt.nyu.edu/scmsAdmin/uploads/006/921/Baumwell%2C%20L.%2C%20Bornstein%2C%20M.%20H.%2C%20Tamis-LeMonda%2C%20C.%2C%20Child%20Dev.%2C%202001.pdf" target="_blank">how good mom was at watching, expanding on, and describing the world</a> based on her baby’s words and gestures. A mom’s responsiveness to her baby’s talk and movements predicted the age at which the babies reached milestones like saying their first words, having 50 words in their vocabularies, putting two words together, and speaking in the past tense. Mom’s response predicted these milestones over and above the baby’s own vocalizations and gestures at those ages. Dr. Tamis-Lemonda, who directs the research, explains that hearing a whole bunch of words doesn’t do a baby much good, unless the parent is actually helping the baby make sense of them. “If parents think, ‘all I need to do is talk,’” she says, “well, that would be a real puzzle for kids. Because what do all those words actually <em>mean</em>?” How do you teach meaning to babies? Between the ages of nine months and two years, the key is to use the baby’s perspective as the springboard for teaching. A three-year-old may be savvy enough to redirect his attention and follow a parent to learn new words, but younger children need the reverse: they need <em>us</em> to follow <em>them</em>. “If the baby is playing with a cup and the parent says, ‘look at the dolly!’ the baby is much less likely to learn that word,” says Tamis-LeMonda. When you talk about the cup, on the other hand, you link visual and tactile information (I see the cup in my hands) with auditory information (hearing the word “cup”). It’s this linking across sensory systems that solidifies learning. Language growth is about quality, not just quantity. For example, in addition to hearing fewer words, <a href="http://www.aft.org/newspubs/periodicals/ae/spring2003/hart.cfm" target="_blank">kids from different backgrounds hear very different <i>types</i> of words</a>. Children in professional families have been found to hear 32 encouraging words and 5 prohibitions per hour on average, while in working class families it’s 12 affirmations and 7 prohibitions per hour, and in families from lower socioeconomic classes, 5 affirmations, but 11 prohibitions. Over four years, that makes almost half a million more instances of encouragement from affluent families, and 125,000 more discouragements in lower-income families. Research suggests that this significant difference in positive versus negative feedback is what attributes to the language gap between classes. Simply put, the more positive affirmations a child receives in conversation, the greater their grasp of language will be. <a href="http://steinhardt.nyu.edu/scmsAdmin/uploads/007/071/Cristofaro%2C%20T.%20%26%20Tamis-LeMonda%2C%20C.%20S.%2C%20Jrnl%20of%20Early%20Child%20Lit.%2C%202012.pdf" target="_blank">Studies</a> also find that qualities like how often moms ask “wh” questions (who, what, when, where, which, why, how) correlate to a child’s language skills and predicts later school-readiness. In other words, it’s easy to take the advice to talk to your baby and run with it, but as conscientious parents we tend to fall prey to the idea that if something is good for our child, more of it must be better. Yes, hearing lots of words is crucial to a baby’s development, because, as Tamis-LeMonda puts it, “the only language they’ll use is the language they hear.” But watching <em>and</em> listening, so you can provide contingent responses, is what research shows to be most powerful. How many times has your baby or toddler started a thought, only to have you jump in and finish it? (I’m guilty of this too). Listening is a skill, and it’s hard sometimes. Listening well means observing your child with curiosity, wondering what she’s going to say or do next, and resisting the urge to interrupt. It means pausing and letting there be silence, but still staying engaged. In fact, research has shown that you don’t need words to encourage your baby’s talking;<a href="http://babylab.psych.cornell.edu/wp-content/uploads/2009/04/goldstein-et-al-2003.pdf" target="_blank"> just smiling, moving closer to your baby, or touching her is enough</a> to immediately make her vocalizations more sophisticated. The other day, I practiced conversing with my 17-month old over lunch by being quiet but watching her round, little face to see where her train of thought would take her. She did plenty of banging her fork on the table, waving avocado in the air, and rotating through both English and Ewok-sounding phrases. But then she started making sounds I hadn’t noticed before. “She’s singing the ABCs,” my husband guessed. We smiled and bopped our heads, but resisted the urge to chime in and join her. Sure enough, she had the rough outline of the alphabet and seemed delighted at the opportunity to perform it for us while we just watched. I never would have known that language was filed away in her rapidly growing brain. Encouragement, but also a little space, gave her the opportunity to share it with me.

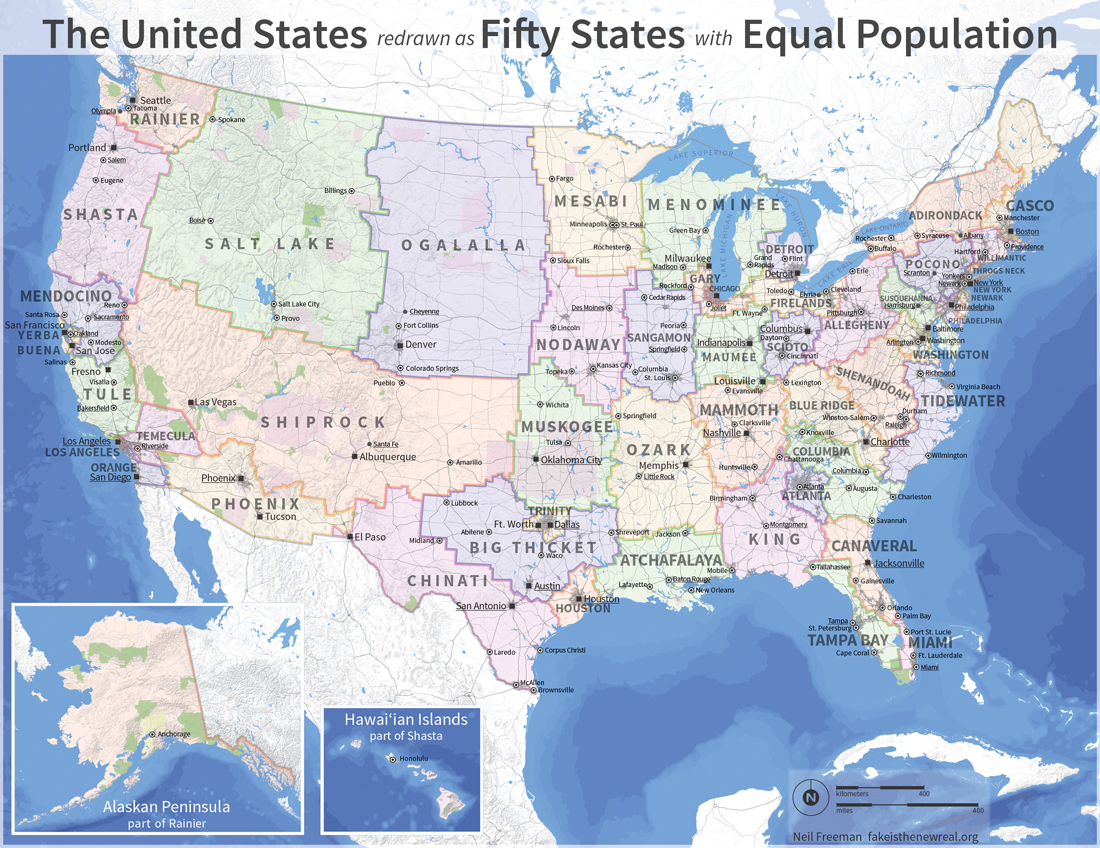

As part of a thought experiment to reform the electoral college, Neil Freeman redrew the US into 50 new states with equal population. In trying to balance the interests of the popular vote vs the integrity of states, he's split the baby so that no one is likely to be happy. Perfect!

The map began with an algorithm that groups counties based on proximity, urban area, and commuting patterns. The algorithm was seeded with the fifty largest cities. After that, manual changes took into account compact shapes, equal populations, metro areas divided by state lines, and drainage basins. In certain areas, divisions are based on census tract lines.

Keep in mind that this is an art project, not a serious proposal, so take it easy with the emails about the sacred soil of Texas.

(via ★doingitwrong)

Tags: maps